|

Wanted Men

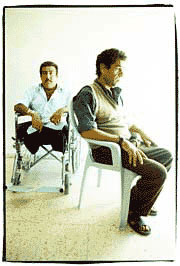

At 11 in the morning last Monday, at the exit from Jenin, IDF soldiers detained two dialysis patients, one a double amputee and the other blind in both eyes. They set the amputee down on the road and had the blind man sit next to him. Both were exhausted after dialysis treatment. The amputee was bleeding from the dialysis tubing in his body. The soldiers sent the men's wives away and left them there on the road for about an hour. Then they transferred them to a detention facility and later to another one. For 10 hours, the IDF held onto these two very ill men, and bounced them around in a jeep from one place to the other, on the suspicion that they could be wanted men. In the evening, they were finally released and sent home, and no one had ever interrogated them during all the hours they were held. The soldiers wanted to leave the blind man in the middle of nowhere and let him find his own way home, and they thought of binding the hands of the amputee, but they changed their minds. When people from the Physicians for Human Rights organization, who are known for their credibility, told me the story, I found it hard to believe. When I went to the remote village of Jeba' this week, to the homes of the two crippled men, I was horrified to discover how low we've now sunk: that soldiers from the IDF could detain men in this condition for long hours, that they could be capable of abusing such broken vessels as Bassam Jarar and Mohammed Asasa, that no soldier or commander or even the military physician who took care of the amputee got up at any point during that day and demanded to know what the hell was going on here, that this is how we could treat these two severely disabled people. And if there were still any doubt about the monstrousness of the story, it was immediately dispelled by the callous response of the IDF spokesman, who said the men were detained "in order to check if they were wanted men." No expressions of regret here. It was all just a technical glitch. Bassam Jarar sits on his wheelchair in Jeba', at the edge of the spectacular Dotan Valley, where the roads are deserted and scary. Both of his legs were amputated at the thigh about two years ago at the hospital in Jenin, after they became gangrenous as a result of his kidney disease. Before he became ill about 10 years ago, he worked as a taxi driver on the Jenin-Nablus route, in the days when Palestinians could still travel freely between these cities. Before that, he worked for years at the Coca-Cola factory in Bnei Brak. He is 42, a father of five, and smiles a lot even while recounting what happened on that awful day. Before saying goodbye, I noticed that the palms of his hands were badly scraped. He'd forgotten to tell me that he had been tossed to the ground by the soldiers and fallen on the asphalt. He told the whole story very calmly and quietly, just as his blind friend did. He has the grayish pallor of all those with kidney disease. Three times a week, he leaves home at 5:30 in the morning to make the long and tiring journey to the dialysis machine that keeps him alive. He has been doing this for 10 years. After each four-hour treatment, he is completely worn out and needs rest. Jarar used to travel to Nablus for dialysis, and recently he'd been going to the new dialysis center in Jenin, which is closer to where he lives. Now both cities are surrounded by the army and the only way he can get there is by ambulance. It takes from an hour to an hour and a half in each direction, of which half the time is spent waiting at checkpoints. He makes the trip on Saturdays, Mondays and Thursdays. Sometimes, 13 patients are crammed into one ambulance. When the IDF entered Jenin in April, the road was completely blocked and he had to spend 22 days in the hospital in Nablus. Approximately 40 more dialysis patients were stuck there with him. Usually, his brothers carry him from his home down to the village road, then drive him to the edge of the Qabatiya cemetery, where, near the checkpoint manned by tanks, he is transferred to an ambulance that has come from Jenin. Mohammed Asasa always travels with him. They're from the same village. Asasa lost his vision about 13 years ago as a result of diabetes. Five years ago, he also contracted kidney disease and has been dependent on dialysis for the past four years. He is 46, a father of 10 and grandfather of one. Despite all he has been through, he also smiles. Before he got sick, he worked transporting laborers to Israel, mostly to Acre. Both Asasa and Jarar speak good Hebrew. Their wives, Fariyal and Nidal, always accompany them to their dialysis treatments. Last Monday, they left as usual at 5:30 in the morning, finished the treatment at 11 and headed home to rest. The ambulance they were traveling in got to the checkpoint at the southern exit from Jenin. The soldiers from the tanks there asked to see the identity cards of all the patients in the ambulance. There were nine dialysis patients with their escorts. After about half an hour of waiting, soldiers got out of two tanks and ordered the ambulance driver to let Jarar and Asasa off. The driver asked where he was supposed to put the blind man and the amputee, and the soldiers told him to put them down on the road. Asasa asked the soldiers to let his wife and his friend's wife stay with them, but they refused and sent the ambulance on its way with the two women and the rest of the passengers. Asasa and Jarar remained alone on the road. About half an hour passed, and then blood started to drip from the tube that is permanently inserted in Jarar's lower abdomen. "I told the soldier on the tank that I was bleeding. He told me to sit there and that they'd take me to a doctor. We sat there in the sun for almost an hour." The soldiers offered the men water, but they declined it. The bleeding increased. After about an hour, two soldiers came and lifted up Jarar and placed him on the floor of their jeep. "I told them that I couldn't travel in a jeep. They said that's all there was and that they were going to take me to a doctor. The guy drove like a maniac and I was bouncing up and down and my whole body hurt. I told them that it hurt. They said, `Don't be afraid, you're not going to die.' There were four soldiers in the jeep and I was on the floor. He wouldn't slow down. And the soldiers were laughing and not looking at me at all. "It took 20 minutes until we got to the doctor at the army camp, I don't know where it was. They took me out and the doctor put on a bandage, but he didn't clean the area. Then the doctor told me that they wanted to take me to detention in Jalameh. I said I wasn't going in a jeep. I was very tired. They brought an ambulance. I went in the ambulance to Jalameh, where the doctor let me out and told me that everything would be fine now. When the doctor left, they came to blindfold me and to bind my hands. I asked them what was the point of tying my hands? Did they think I was going to run away? Without legs? So they didn't tie my hands, but they did blindfold me. "We stayed there until about nine in the evening. And I started to bleed again. I was yelling that I needed a doctor and the soldier there was reading a newspaper. They said just to wait five more minutes, but they didn't bring anything. I didn't eat or drink. I just asked for a cigarette and the soldier gave me one. "At seven in the evening, they said, `We're going to take you in a bus to Salam.' There were 26 other detainees who'd been there since four in the morning. They wanted to take me in a bus and I yelled that I wasn't getting on a bus. I told them to either bring an ambulance or kill me. They all went on the bus except for me. I stayed there alone on the floor. And I was bleeding the whole time. I kept saying, `Get a doctor! Get something to stop the bleeding.' I started shouting and shouting, but the soldier kept reading his newspaper." Asasa was taken in a separate jeep to Jalameh and still feels the effects of the bumpy ride. He says that since then he hasn't been able to sit comfortably because of the pains in his back. After three or four hours of waiting on the floor in Jalameh alongside his friend, Asasa was put on the bus to Salam. When he asked where Jarar was, he was told that he'd been left behind. Asasa was worried. "They wanted to tie my hands and I have a tube for the dialysis on my wrist and I told them that if they tie me like that, I'm finished. I also told them not to put anything over my eyes, since I can't see anyway. So they didn't put anything. At Salam, they let us off and made me sit on the floor again. I kept asking, `Where's an officer? It's hard for me to sit. I can't sit,' and the soldier said that I had to wait to be seen by the Shin Bet. I told him to bring me there already, and they told me to sit and wait. At 9:30, a soldier came and said, `You can go home now.'" The IDF spokesman: "On the afternoon of Monday, October 28, an IDF force that was conducting an operational action in the city of Jenin stopped a Palestinian ambulance to search it. The ambulance was stopped due to the suspicion of the soldiers at the checkpoint that it was carrying wanted men. As a rule, Palestinian ambulances are allowed to move freely in Judea and Samaria, but due to the increase in instances in which ambulances have been used to transport weapons and wanted men, especially in the past two weeks, IDF soldiers have been instructed to conduct a brief examination of their passengers and cargo before permitting the vehicles to continue on their way. "In this case, because a technical problem with the communications equipment made it impossible to check on the spot whether these were wanted men, the two Palestinians were transferred to a nearby facility and when it was determined that the two men were not suspects, they were released. It should be noted that the two Palestinians were not on an urgent trip to the hospital but on a routine trip back to their homes." A soldier told the blind Asasa that they'd let him off in Rumaneh, a kilometer and a half from the checkpoint. It was already 9:30 at night. "I said, `I'm blind. How will I get home? Take me there.' He said that he couldn't. I told him that I was staying put then. Then I asked him to bring an officer, and that I was so tired and just wanted to get home. He said that he'd bring someone soon and that I'd be taken to Jalameh. A Border Police jeep showed up about an hour or an hour and a half later. I asked the Druze police officer to use his cell phone to call and arrange for the Jenin ambulance to come pick me up in Jalameh. The ambulance brought me to the cemetery and my son and wife were waiting for me there. I didn't feel well. I always sleep after dialysis and we'd been on the floor for 10 hours. I still can't sit comfortably because of the pains from that day." At 9:30, an ambulance was also called to pick up Jarar. He was taken straight to the hospital in Jenin to get his bleeding under control. His hemoglobin was dangerously low. "Believe me, if I'd been there another hour, I'd be dead," he says. He finally returned home after 11 at night, 18 hours after he set out in the morning and 12 hours after he was first detained. On the way back, the soldier who had stopped Jarar in the morning asked him how he was feeling. Jarar didn't answer. "I wanted to show you that our doctors are better than your doctors," the soldier joked to the dialysis patient who'd almost bled to death after being put through the day's horrendous ordeal because some soldiers thought that he and his blind friend might be dangerous suspects, and couldn't be sure because their radio happened to break down. http://www.miftah.org |